CASE STUDY: Catching hidden PFAS-like structures with pfasID

PFAS management is often treated as a matter of compliance: check the lists, confirm whether a chemical appears, and move forward if it doesn’t. But as PFAS definitions evolve and regulatory frameworks struggle to keep pace with chemical innovation, list-based screening alone is no longer sufficient to prevent risk.

Increasingly, product teams face a more subtle challenge of chemicals that fall outside formal PFAS lists, yet still contain fluorinated structures associated with persistence and long-term concern. These “hidden” substances with PFAS-structural features can quietly slip through early screening processes, creating the risk of regrettable substitution later.

The following case study illustrates how structural screening, rather than reliance on static regulatory lists, can surface these early warning signals. By applying pfasID’s molecular fingerprinting approach, one team was able to identify PFAS-like characteristics before a material entered their product pipeline, avoiding downstream risk and uncertainty.

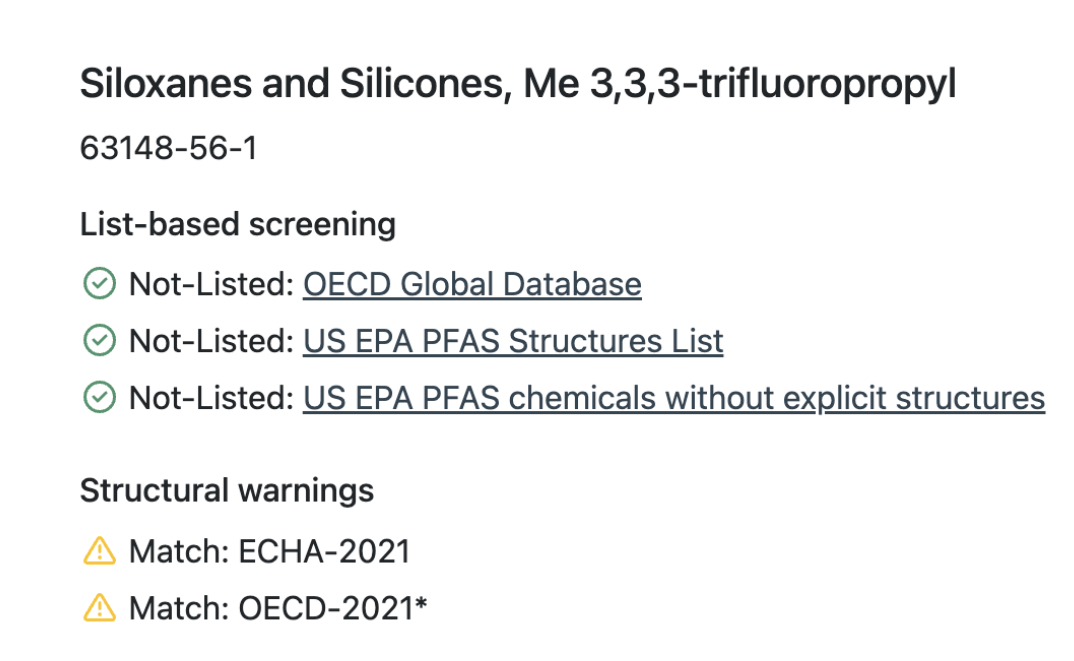

A product team working to phase PFAS out of their supply chain recently evaluated the chemical Siloxanes and Silicones, Me 3,3,3-trifluoropropyl [CAS: 63148-56-1] to determine whether it constitutes a PFAS material and therefore should be targeted for substitution. The chemical did not appear on established PFAS databases, including the OECD Global Database and those from the US EPA. Based solely on list screening, it initially seemed to be a feasible non-PFAS option.

A closer look at the detailed results shows how pfasID surfaced these PFAS-like structural warnings.

A closer look at the detailed results shows how pfasID surfaced these PFAS-like structural warnings.

When the team screened the chemical through pfasID, the platform quickly surfaced a structural warning aligned with both ECHA and OECD structure-based definitions. Through molecular fingerprinting, pfasID identified the compound’s carbon-fluorine bonds and flagged it as structurally consistent with certain PFAS-like chemistries, despite its absence from regulatory lists. This early signal–initially missed by list-based screening–prompted the team to pause and re-evaluate the material before adoption.

This intervention helped the team avoid a potential regrettable substitution: selecting a material that technically falls outside formal PFAS lists, but still contains structural features associated with long-term persistence and potential environmental or human health toxicities. By surfacing these early structural flags, pfasID enables teams to stay ahead of evolving definitions, and prevent PFAS-structured substances from entering their product pipeline.

To explore how structural screening can help identify PFAS-like characteristics early, sign up for free access to pfasID at www.pfasID.org.

You can try screening the example highlighted here:

Siloxanes and Silicones, Me 3,3,3-trifluoropropyl [CAS: 63148-56-1]

Poly(vinylidene difluoride) [CAS 24937-79-9]

2-[[2-[N-Acetyl-3-(trifluoromethyl)anilino]-3-methylbutanoyl]amino]acetic acid [CAS 379685-96-8]

If you’ve encountered similar cases, we invite you to share anonymized examples to help others in the community avoid regrettable substitutions.